The Ghosts of the Mountains caught on film by WWF researchers

Rinjan Shrestha, Conservation Scientist for WWF’s Eastern Himalayas Programme shares his experience from a recent expedition to track snow leopards and why camera traps are crucial tools for counting snow leopards.

After a gruelling six days on foot, our expedition finally reached an altitude of 4,500 metres – and the home of the endangered snow leopards of the north central region of Bhutan. Snow leopards, also known as the ‘ghosts of the mountains’ for their puzzling elusiveness, are among the least known cats of the world.

In addition to the elusive behaviour, their sparse distribution and the remoteness of their habitat have all contributed in making them one of the most challenging animals to study. Yet conservation managers urgently need to know how many snow leopards there are – and whether their numbers are increasing, decreasing or remaining stable – in order to devise strategies to secure the snow leopard’s future survival. And that is why I climbed the 4,500 meters with my team in the Wangchuck Centennial National Park of Bhutan: To count them.

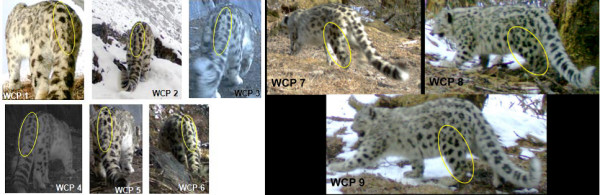

Thanks to the unique spot patterns on their body coat, it is now possible to count snow leopards using automatic hidden cameras. These cameras are fitted with motion and heat sensors, and as such they take pictures of any moving objects having a different temperature than the surrounding environment.

Our first order of business was to locate the sites where snow leopards are likely to be found. Past experience tells us that snow leopards most commonly use travel paths that pass through cliff bases, mountain passes and ridgelines.

We began setting up the camera traps after selecting the most appropriate sites. The cameras are positioned to take pictures mainly of body parts such as head, lower legs and tail of snow leopard. It is important because these sections of a snow leopard’s body do not possess a thick layer of fur, which would otherwise make individual identification very difficult due to the distortion of spot patterns.

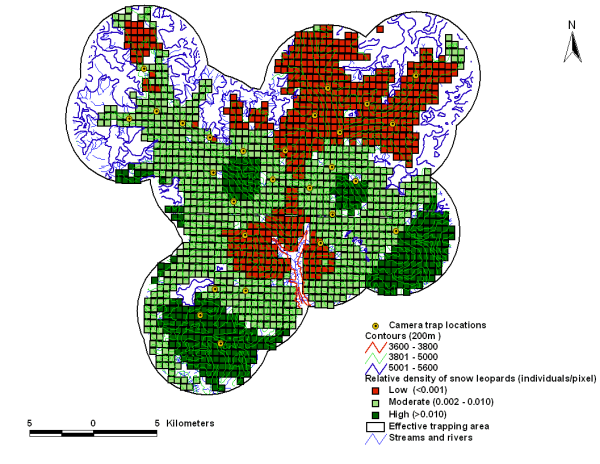

It took us nearly a month to set up a total of 27 camera trap stations across the 800 square km study site. These cameras were to remain out in the field for at least two months.

I came back to Toronto after setting up the camera traps and waited impatiently for any news from the field. A call from Bhutan on one fine morning was like a music to my ears: Our cameras had captured not only snow leopards, but also many other interesting animals. Some, such as the Manul cat (Pallas Cat), represent new records for Bhutan Himalayas. People often confuse Manul with a monkey at a quick glance. Manul is regarded as one of the most primitive animals on this planet that has not changed over 6 million years!

We now have 1,013 pictures of snow leopards including two family groups. The presence of breeding populations of snow leopard signified that Wangchuck Centennial National Park is the core snow leopard habitat in the Eastern Himalayas.

Following an intensive study of spot patterns we identified nine different individuals of snow leopard. The cross verification of photo identification were facilitated by three WWF-Canada volunteers. Thus we came to know that there were at least nine individuals of snow leopards present in the study site. But we also know that not all the snow leopards that were present in the study area would have been captured by our camera traps. Therefore, in order to estimate the number of snow leopards that were not detected by the automatic camera and thus to estimate the total population, we implemented a statistical procedure known as Capture-Recapture Analyses. The analyses revealed that the snow leopard numbers in the park vary between nine and eleven individuals. We also estimated density of snow leopards so as to facilitate the comparison across places and time periods. The density turned out to be 2.31 individuals per 100 square km.

This study carried out in collaboration with the Government of Bhutan and WWF’s Asia High Mountains Project is the first systematic assessment of snow leopard population in the park. As such it sets an important milestone in efforts to conserve snow leopards in Bhutan. The study provided base line data to enable the park managers to measure successes and failures of conservation initiatives in the days ahead.

On November 25, 2013, we were able to fit satellite collars to a snow leopard for the first time ever in Nepal. WWF in partnership with government of Nepal and National Trust for Nature Conservation are currently monitoring the satellite telemetry operation. These collars will help us to learn even more about these rare big cats – and hopefully, safeguard them for generations to come.

Learn more about our snow leopard work and find out how you can help.

The full length documentary about this expedition and the telemetry operation will be available online in the coming months.