Extremely loud and incredibly close: seismic tests in Atlantic Canada will hurt endangered whales

I know it sounds silly, but when I’m out to sea studying whales, I’ve often found myself trying to picture what their lives must be like – how it must feel to take that big gulp of air, lift their tails way up, and turn their bodies down into the dark water to dive down and find food.

In the case of the endangered northern bottlenose whale, a species I studied for my Biology Master of Science degree in Nova Scotia, this has always astounded me because, as one of the world’s champion divers, they regularly dive to depths of over 1000 meters and can stay down for over an hour at a time!

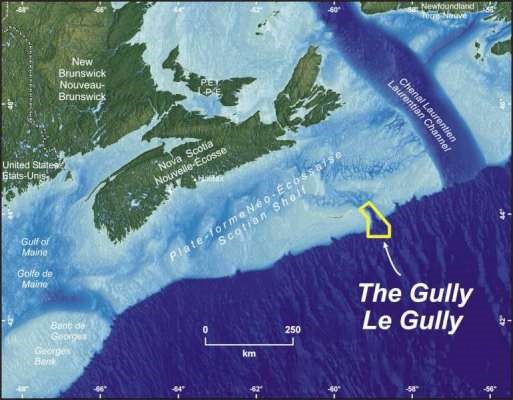

I was part of Professor Hal Whitehead’s team at Dalhousie University which have been researching the species since 1988 – the first and longest running project on a beaked whale species anywhere in the world! Because of this long-term research, we know that there are only about 160 individuals in this population, that they predominantly live in three underwater canyons on the Eastern Scotian Shelf – the Sable Gully Marine Protected Area as well as the Shortland and Haldimand canyons. They don’t really move around much or mix with other populations further north off Labrador and Iceland. So if these areas are disturbed, the whales have nowhere else to go.

Recognizing the small population, restricted habitats, limited movements, and growing threats from fishing and noisy seismic testing, Canada listed northern bottlenose whales as Endangered under the Species At Risk Act (SARA) in 2006. The Gully – which celebrates its 10th anniversary as a protected area this week – and Shortland and Haldimand canyons were also put under government protection to ensure this increasingly rare species had a natural safe haven.

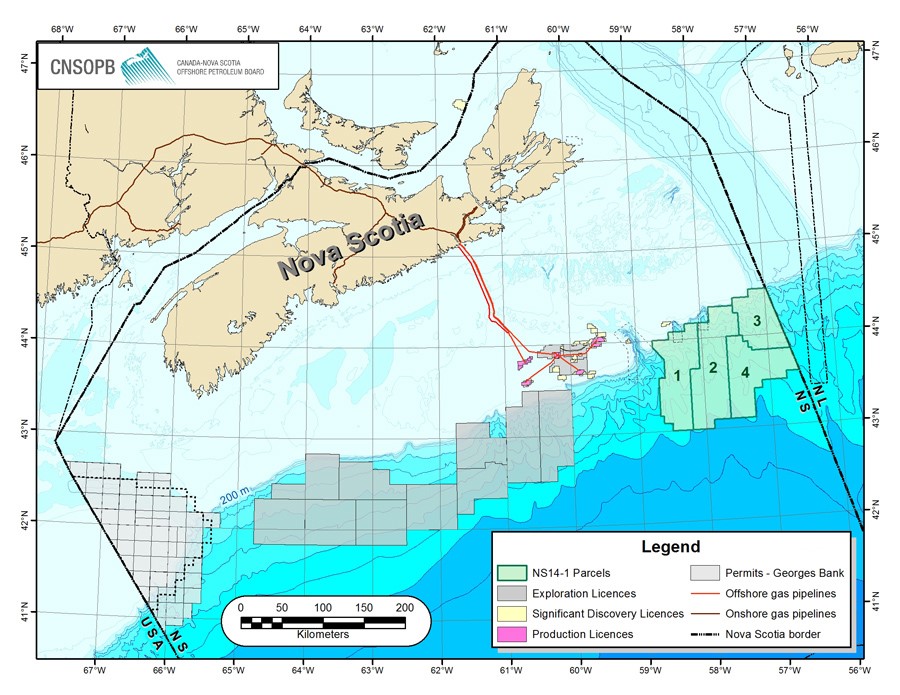

But these safe havens are again under threat from oil and gas exploration in and around their borders. On May 5th 2014, the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board (CNSOPB) issued a call for bids that could result in new seismic exploration licenses near these protected areas, threatening to blast apart decades of work that lead to heightened protection of the Gully and neighbouring canyons.

Our concern with seismic exploration taking place close to critical habitats like the Gully is that cetaceans communicate, with each other and with their babies, by bouncing sound off things. They also use sound to navigate and locate predators and prey. There is mounting evidence that loud noises produced by human activities – including seismic, shipping and many others – can cause serious disturbances that mask their calls and force them out of the areas they typically live in. In some cases, whales have died due to injuries sustained from exposure to the powerful pressure wave created by loud sound sources.

Simply put, our lack of knowledge on the impacts of seismic and the presence of these and other endangered species should be enough to stop seismic testing in the home range of cetaceans and other vulnerable wildlife until more is known.

Canada has national commitments, including SARA and the Oceans Act, and international ones, including the Law of the Sea Convention and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, to protect species at risk and their habitats through the protection of key areas and the establishment of networks of protected areas. To date, Canada does not have a good track record of fulfilling those commitments.

Seismic testing has no place in critical habitats of cetaceans, particularly when they don’t have another place to go, like Scotian Shelf northern bottlenose whales. WWF believes that seismic testing shouldn’t be allowed around critical habitats until proper baseline scientific research, conservation buffer zones, and monitoring programs are established. We also think that petroleum companies should not bid on these leases to help protect this endangered species.

Part of what makes Canada so great is that we have an astounding natural heritage with a plethora of species and habitats. We need to ensure they, like us, have a healthy home. That’s something to celebrate – both on the Gully’s 10th anniversary this week, and for the many milestones that we’re working with supporters to achieve.